|

Nulla Dies Sine Linea

No Day without a Line 13. February – 19. March 2016 Based on an idea by Gaby Hartel |

NULLA DIES SINE LINEA

No Day without a Line

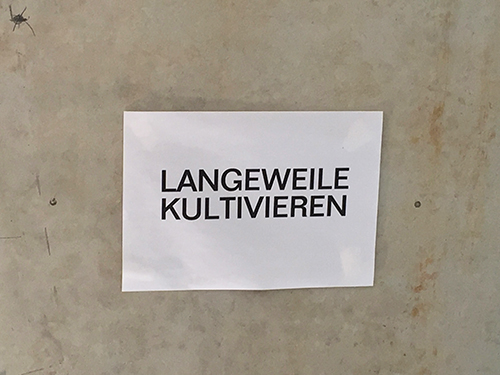

The creative mind often relies on rituals to enable it to retreat, draw inspiration from what it has sensed and create new forms. As the name of this exhibition implies, daily practice might be one of those rituals. But today’s fast-paced, digital age distracts with constant connectivity to the outer world. Observing, feeling, listening, contemplating and reacting––at times all at once––require full engagement of the senses. Conscious discipline becomes essential to access one's inner world.

NULLA DIES SINE LINEA was conceived as an open-ended exhibition to examine the idea of the ‘practiced mind’ as a path to inspiration. “No day without a line [drawn]“ is a saying attributed by Pliny the Elder to the ancient Greek painter Apelles, who was famously diligent in practicing his art every day. In this spirit, our show aims to examine the habits and practices used by agile thinkers to stay connected, or ‘in line,’ with the sublime. If this ‘line’ represents a kind of key to the creative self, questions arise: What state of mind is necessary to come up with an idea for an artwork, a musical composition, the next sentence or verse, or a new theory? How does one access it on a regular basis? Most importantly, what role does daily routine play?

We invited artists, authors, scientists, philosophers and doyens to share their practices with us and contribute to our experimental show. SATELLITE BERLIN’s space became a threshold to the creative process–– a room, in which to listen and gain insight into fertile minds or to enter one’s own. We received 38 contributions and added them day by day as they came by mail or were brought by or were installed by artists. The way they visually conjoined, overlapped and corresponded reflected the richness of the many voices heard, the variety of stillness that are the origins of individual creativity.

We thank all the participants, the agile thinkers, for their unique contributions and hope this publication will bear witness to quotidian workings of the creative mind.

Kit Schulte and Rebeccah Blum

No Day without a Line

The creative mind often relies on rituals to enable it to retreat, draw inspiration from what it has sensed and create new forms. As the name of this exhibition implies, daily practice might be one of those rituals. But today’s fast-paced, digital age distracts with constant connectivity to the outer world. Observing, feeling, listening, contemplating and reacting––at times all at once––require full engagement of the senses. Conscious discipline becomes essential to access one's inner world.

NULLA DIES SINE LINEA was conceived as an open-ended exhibition to examine the idea of the ‘practiced mind’ as a path to inspiration. “No day without a line [drawn]“ is a saying attributed by Pliny the Elder to the ancient Greek painter Apelles, who was famously diligent in practicing his art every day. In this spirit, our show aims to examine the habits and practices used by agile thinkers to stay connected, or ‘in line,’ with the sublime. If this ‘line’ represents a kind of key to the creative self, questions arise: What state of mind is necessary to come up with an idea for an artwork, a musical composition, the next sentence or verse, or a new theory? How does one access it on a regular basis? Most importantly, what role does daily routine play?

We invited artists, authors, scientists, philosophers and doyens to share their practices with us and contribute to our experimental show. SATELLITE BERLIN’s space became a threshold to the creative process–– a room, in which to listen and gain insight into fertile minds or to enter one’s own. We received 38 contributions and added them day by day as they came by mail or were brought by or were installed by artists. The way they visually conjoined, overlapped and corresponded reflected the richness of the many voices heard, the variety of stillness that are the origins of individual creativity.

We thank all the participants, the agile thinkers, for their unique contributions and hope this publication will bear witness to quotidian workings of the creative mind.

Kit Schulte and Rebeccah Blum

A chapter illustration of a book on drawing from 1643 depicts its content as a highly complex, self-referential image: a gloved hand seemingly growing out of the form that frames it—a wreathe of bay leaves bound at its lowest end with two crossed feathers. The wreathe being, of course, an emblem of fame and glory which is in our case connected to a symbol of the activity in which the student of the said book wishes to excel.

Since the book is addressed to draughtsmen, the gloved hand leaves a trace on an otherwise empty plane: the schema of a human head. Then, the author himself—pedagogue that he is—leaves a precious piece of advice, so precious that it is written in two different languages and in two different fonts: “Nil cabone sed vju”—“Nulla dies sine Linia.”

This thought has been recorded by Pliny the Elder and it is valid to this very day. What it entails is that--

artist or no artist—we seem to need to scatch the foil of the everyday in a repetitive rhythm to leave a physical trace in order to get ready and function in our respective fields.

Leafing through artists’ sketchbooks, I often sense that while drawing a repetitive pattern, line or theme they start circling in on what they see and feel, on their prevalent topics, their memories and interests, while their creative mind is preparing to seize the moment when, they might start to work “for real.” The moment when, in a paradoxical state of expectant passiveness, they suddenly perceive a chance to turn the flow of ordinary perceptions into something solid and contained. Into a specific form. Into an artwork. The activity need not necessarily consist of drawing or painting. It might be reading or running, walking or doing exercises. The important thing seems to be that the activity is a physical act, an interacting with the grainy materiality of our surroundings. To the tactile eye and the sensitive hand, the existence of texture is a satisfying physio-aesthetic experience, one which William Hogarth referred to as a state of bliss found in irregular and winding lines, which he promoted to his celebrated “line of beauty and grace.”

Repetitiveness in drawn lines or following a series of letters that make up a book may invite us to step into life. The movements of our eyes and hands evoke emotive echoes in our brains. Our fingers read, our eyes read and so does, finally, our intuitive intellect.

Leaving a trace every day in the same way gives us a feeling for the material world, thereby helping us to viscerally understand it. To get a grasp on it.

Since the book is addressed to draughtsmen, the gloved hand leaves a trace on an otherwise empty plane: the schema of a human head. Then, the author himself—pedagogue that he is—leaves a precious piece of advice, so precious that it is written in two different languages and in two different fonts: “Nil cabone sed vju”—“Nulla dies sine Linia.”

This thought has been recorded by Pliny the Elder and it is valid to this very day. What it entails is that--

artist or no artist—we seem to need to scatch the foil of the everyday in a repetitive rhythm to leave a physical trace in order to get ready and function in our respective fields.

Leafing through artists’ sketchbooks, I often sense that while drawing a repetitive pattern, line or theme they start circling in on what they see and feel, on their prevalent topics, their memories and interests, while their creative mind is preparing to seize the moment when, they might start to work “for real.” The moment when, in a paradoxical state of expectant passiveness, they suddenly perceive a chance to turn the flow of ordinary perceptions into something solid and contained. Into a specific form. Into an artwork. The activity need not necessarily consist of drawing or painting. It might be reading or running, walking or doing exercises. The important thing seems to be that the activity is a physical act, an interacting with the grainy materiality of our surroundings. To the tactile eye and the sensitive hand, the existence of texture is a satisfying physio-aesthetic experience, one which William Hogarth referred to as a state of bliss found in irregular and winding lines, which he promoted to his celebrated “line of beauty and grace.”

Repetitiveness in drawn lines or following a series of letters that make up a book may invite us to step into life. The movements of our eyes and hands evoke emotive echoes in our brains. Our fingers read, our eyes read and so does, finally, our intuitive intellect.

Leaving a trace every day in the same way gives us a feeling for the material world, thereby helping us to viscerally understand it. To get a grasp on it.

Gaby Hartel

Berlin, May 2016

Berlin, May 2016

|

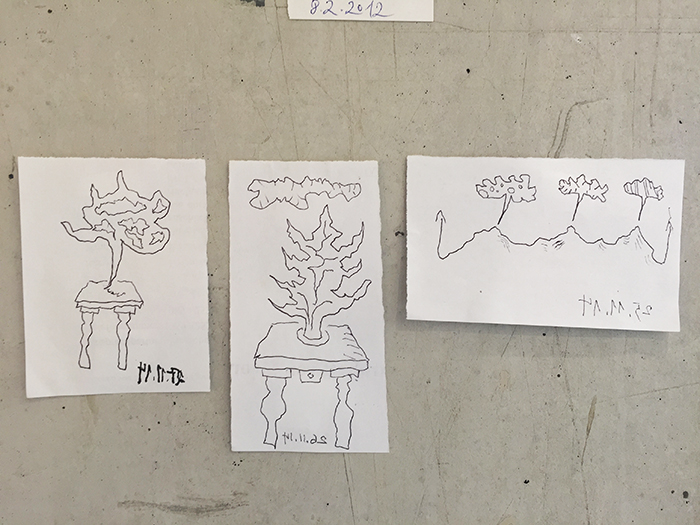

No. 1

Werner Linster Artist, Berlin Nulla dies sine linea - the requirement of not letting a day pass without having drawn a trace or a line, i.e. without a short exercise in one’s own skill, is part of the intuitive knowledge of every athlete and artist. ‘Nulla dies’ ... was said in antiquity, as passed down by Pliny the Elder; ‘practice and repetition’ is said by our contemporary Richard Sennett. My diary-like drawings are doodles done quickly every morning. Are the first play of my working muscles. Are the concentration of my interests, my thoughts. |

No. 3

Tom Chamberlain

Artists, Mexico City

Don’t you wonder sometimes…

I can’t really work in the studio without the radio on. It’s not that I listen to it, particularly; it comes in and out of focus. The sort of concentration I need is something like an abandon. Music is too overpowering, and with the radio I get a kind of silence that doesn’t fill up with the debilitating noise of anxiety and self-consciousness.

Radio 4 is mostly talk, chatter, current affairs, documentaries, some awful radio plays, some good ones. In the to and fro between hearing it and listening to my work and where it might take me, I have to acknowledge that true sublimation isn’t one thing over here and something else over there and out of reach. Rather it’s the combination of both, at the same time. It also seems to explain why many apparently compelling ideas happen while doing something like washing a brush.

Drifting into my solitude, over my head.

David Bowie

Tom Chamberlain

Artists, Mexico City

Don’t you wonder sometimes…

I can’t really work in the studio without the radio on. It’s not that I listen to it, particularly; it comes in and out of focus. The sort of concentration I need is something like an abandon. Music is too overpowering, and with the radio I get a kind of silence that doesn’t fill up with the debilitating noise of anxiety and self-consciousness.

Radio 4 is mostly talk, chatter, current affairs, documentaries, some awful radio plays, some good ones. In the to and fro between hearing it and listening to my work and where it might take me, I have to acknowledge that true sublimation isn’t one thing over here and something else over there and out of reach. Rather it’s the combination of both, at the same time. It also seems to explain why many apparently compelling ideas happen while doing something like washing a brush.

Drifting into my solitude, over my head.

David Bowie

|

No. 4

Ciprian Muresan Artist, Cluj I have a dog and a cat in the studio where I work. I recently moved my studio to my home. From 2009 till January 2016 I had my studio at the Paintbrush Factory in Cluj—a place of creation for a community of 50 artists and perfomers. Till last year, when three galerists (from Sabot, Bazis, Intact) took the name and the brand Paintbrush Factory and registered it as a trademark and we—the artists—can no longer use it. But coming back to the cat and the dog: I feel comfortable when they are around. |

|

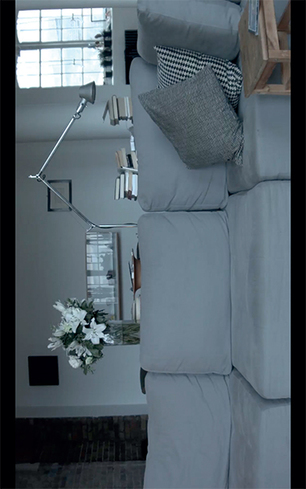

No. 5 Veronike Hinsberg Artists, Berlin There is always a bouquet of flowers on my table. Observing the flowers, I notice the unique character of the different varieties. I compare the characteristic composition of the blossoms, the geometry of the leaves and the various angles of the umbels’ branching. The variety of forms and the spaces created between the branches encourage me to study them more closely. The splendor of their colors and their beauty delight me as I pass. |

|

No. 6 Michael Kutschbach Artist, Berlin Walking at our own pace creates an unadulterated feedback loop between the rhythm of our bodies and our mental state…. Because we don’t have to devote much conscious effort to the act of walking, our attention is free to wander—to overlay the world before us with a parade of images from the mind’s theatre. Ferris Jabr, “Why Walking Helps Us Think,” The New Yorker, Sept 3, 2014. |

|

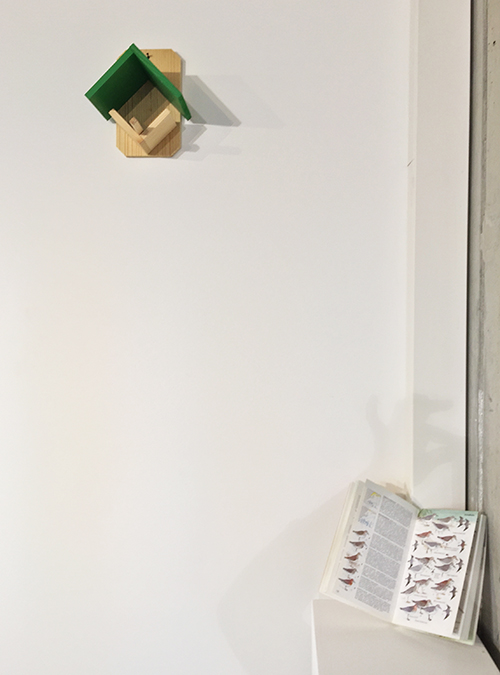

No. 7

Dr. Mark Gisbourne Curator, art historian, critic, Berlin Marcel Proust, In Search of Lost Time (À la recherché du temps perdu)—a novel in seven volumes written from 1909 to 1922: volumes published from 1913 to 1927. Many readers have called Marcel Proust’s masterpiece of social relations and involuntary memory the greatest novel written in the twentieth century, and I would certainly admit to being among them, since I read pages from it every day of my life—at least for the last thirty or more years. When I travel a volume is always with me. It is a novel of seven volumes, 3,031 pages, 1, 267,069 words, and this might suggest that it is an arduous read and feat of endurance to accomplish a single reading, particularly in the current world of twitter and tweets. After all, the most famous rejection of the book by Anatole France was “life is too short, and Proust is too long.” This was the case of Andre Gide’s most famous initial dismissal (later regretted) of the text. But like all great literature, it is self-revealing, for it reads the reader as much as the reader reads the authorial aspect of the novel, for when you come to the end you begin again, and it has somehow miraculously become a new novel all over again. You may think you know the characters, but the subtle variations of perception thrown up by re-reading are almost endless. And it is at the same time an essential delight and a driven insight into miraculous intuition of the writer Proust. If Joyce presents an effulgent stream of consciousness a flowing river of sporadic thoughts and apostasy, Proust presents the framework of consciousness, itself as the continuous process of existent being and anxious imagining. |

I love so many of the literally hundreds of characters from the Baron Charlus, to the ubiquitous Morel, from Swann to Odette de Crecy, the rich, snobbish and pretentious Monsieur et Madame Verdurins and so on and on in subtle differentiations. And as any reader might, I imagine myself as the narrator participating in the shared and speculative libidinal insights into his love of Gilberte and Albertine. And this unique insight is the case notwithstanding that Proust’s actual gender orientation was distinctly otherwise directed. But most of all, the characters that I return to again and again through the variegated imaginings of the narrator are Oriane, Duchesse de Guermantes, and the Marquis Robert de Saint-Loup-en-Bray. Like all his characters, they are complex and multi-faceted, and similarly based on an amalgam of living persons known to Proust. One like an imagined figure of history, the other a figure of modern paradoxical complexities. And these are the two characters I regularly bring to mind in my daily life—relative yet paradoxical opposites. Therefore in the Satellite project Nulla Dies Sine Linea, or in my case ‘nulla dies sine linea legere,’ I have asked that the members of the gallery re-enact the roles of Oriane and Robert in their daily work lives at the project space, that is, through the exhibition period of 13th February to 19th March, 2016, and at the same time undertake reading lines from Proust everyday during the exhibition period. |

Mark Gisbourne and his contribution,

Rebeccah as the Marquis Robert Saint-Loup-en-Bray |

|

No. 8

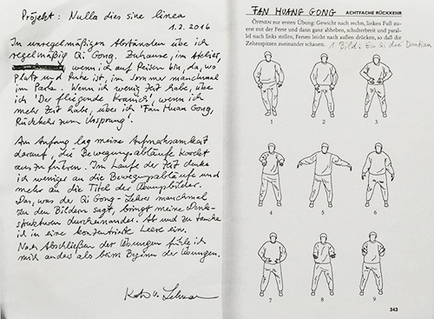

Katrin von Lehmann Artists, Berlin With irregular regularity I practice Qi Gong. At home, in the studio, when I’m travelling, wherever there is space and calm, sometimes in the park in the summer. When I have little time, I practice the “Flying Crane.” When I have more, I practice “Fan Huan Gong Return to the Source.” In the beginning, my attention was focused on executing the movements correctly. Over time I thought less about the movements and more about the title of the exercise. What the Qi Gong teacher occasionally says about the exercise’s title confuses my thought structure. Now and then I become immersed in a concentrated emptiness. After finishing the exercises I feel different from when I began the exercises. |

|

No. 9 Dr. Konstantinos Katsikopoulos Cognitive research scientist, Berlin My job is to research how ordinary people come up with clever shortcuts for reasoning and making decisions. These shortcuts tend to be simple—sometimes borderline naïve—but often outperform the complex mathematical models developed in statistics, management science, and artificial intelligence. So I think about people’s thinking all the time. A lot of this thinking is active, but some of it is passive. In the morning, I spend time watching people. As Kate Bush said, people are amazing, just full of inspiration. I first look outside my window. I see people walking, riding bicycles, getting in and out of cars, going to school, going to work, opening up their stores. That’s how it looked today. After I leave home, I do some more people watching. When I am out, I like to combine people watching with thinking about the technicalities of my research. I may go to a café with a scientific article, alternating between reading and watching. Resting my eyes off the page helps to think. That’s what I saw today. |

|

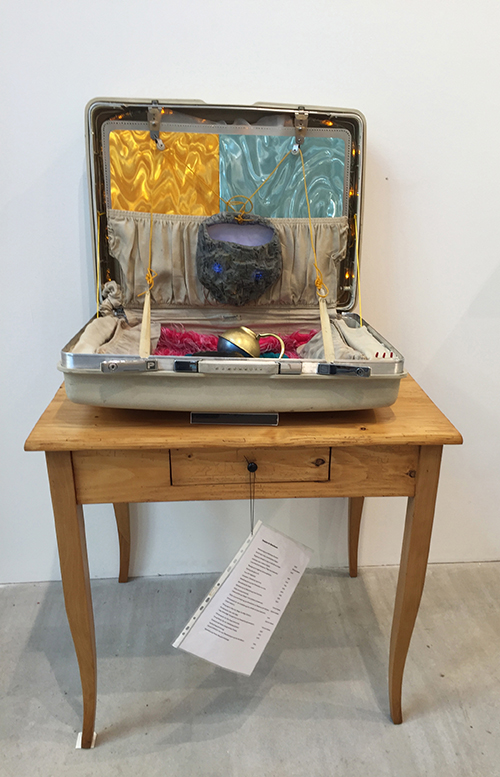

No. 10

František Skála Artist, Prague Price List for Ritual Services Invocation of a talentless artist - 1000 € Initiation of a trance-like state - 90 €/min+expenses Inspiration (birth of an idea without using Google) - 500 € Clearing out a nasty mood (3 days no social media) - 950 € Disposal of negative creative impulses - 500 € Finding of one’s self - 780 € Pudenda of originality - 800 € Mucking out (initiation of) the studio - 450 € Incense of a worktable from below - 450 € Initiation of equipment - 480 € Initiation and invocation of a computer - 560 € Silent author worship (telepathically– without physical presence) - 90 €/min+expenses Silent author worship (in adjacent room, by order of others) - 90 €/min+expenses Intercession for a work’s enrichment with a flash of genius - 300 € Intercession above the cradle (future artist) - 90 €/min+expenses Intercession above the coffin (living legacy and price increase mechanism) - 90 €/min+expenses Intercession for grant bestowal - 280 € Intercession for residency - 270 € Submission of a successful project - 235 € Partner invocation - 300 € Initiation of a favorite pet - 200 € |

|

No. 11

Lothar Götz, Artists, London seven tea cups for seven days The transition from night to day or dream to reality is crucial to me. If I get it wrong the day is basically fucked, if I get it right the day is full of ideas. Tea in the right cup always helps to get over it, but which cup is the right one? Without really noticing, I started to get into the habit of spending a few minutes every morning sourcing for the right cup to start the day. The ideal cup will set me in the right mood and different days need different cups. I love the conversation with the abstract shape of a tea cup, and I carry it with me into my day and studio. |

|

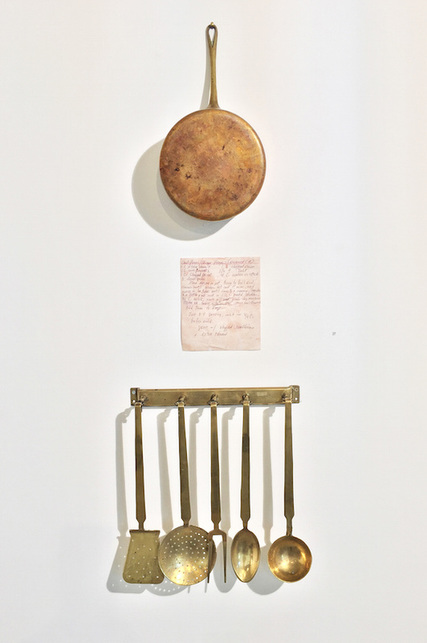

No. 12

Jonathan Turner Curator, art critic, Rome Cooking the Books: or what role my kitchen plays in my creative juices In my kitchen, there is always a lot of marinating, reducing, simmering and percolating going on. When I sit in my studio in front of my computer to write a review or a catalogue text, hopefully the same things are fermenting in my mind. The two procedures work best in tandem. Cooking and writing—for me they are often linked. Already for decades, I repeat a daily ritual which kick-starts the process of invention. I wake up early, and walk a couple of blocks from my apartment in the Trastevere area of Rome, to the daily fruit and vegetable markets in Piazza di San Cosimato. It’s a hard-working market, nothing fancy, but with incredibly fresh produce often sold by the families of the farmers themselves. I rarely decide in advance what I am going to buy, and the quantities are always different, because I usually have guests coming over for lunch or dinner on my terrace. I always shop at the same market stall, run by Bruno, Virginia, Fabio, Davide and various cousins, and they make jokes as they suggest the best of the seasonal greens. They banter, I barter, we laugh. It’s the stuff that inspiration is made of. Depending on the season, I buy a veritable A-to-Z, from artichokes to zucchini, plus cherries, lemons, mushrooms, or such local greens as puntarelle, wild rughetta or frigitelli. It affects my mood. If my phone has been ringing, or there are messages to answer, I sometimes I stop off at the bar San Calisto on my way back home, for a prover-bial Pieroni beer. People tell me their gossip. They always do. And it’s always cynical but affectionate. I walk up the stairs back to my apartment, unpack the shopping bags, stand at the kitchen bench to chop, dice, slice and grate. Then I start to cook something on the stove. Now I am ready to start something on my computer screen. The basic, almost instinctive act of shopping and cooking food each morning provides the initial stimulus for the much more anti-social act of tunnel vision. For me to write cohesively, it helps that all the other senses have already been exercised, and the smells that now drift from my kitchen add spice to my vocabulary. Flavour is heightened. Also, I maintain that the generosity of preparing a meal generates a more open, healthy attitude to accompany my critical eye. I consider myself to be relatively pragmatic, and I seek to write in a manner, which is descriptive, emotional but clear. To construct even a simple menu is a perfect start-up, a departure point, to create a pungent tone from ingredients and cooking methods, eventually helping me to shape the mood of my writing for the day ahead. |

|

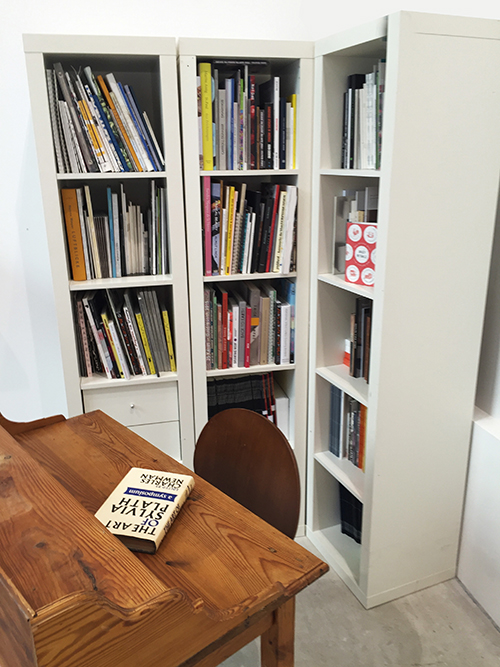

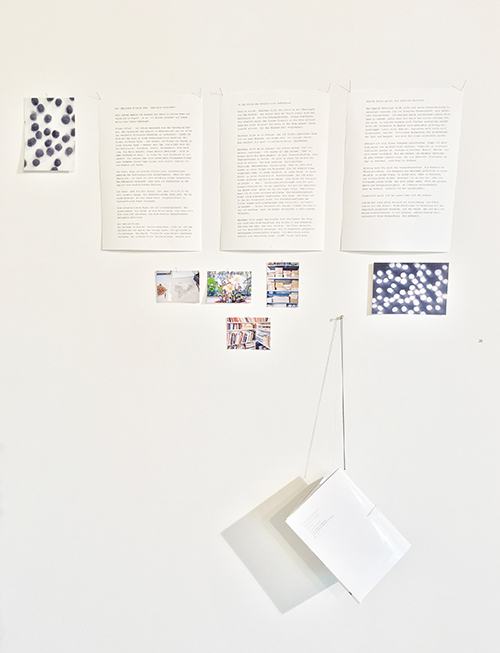

No. 13 Tamar Yoseloff Poet, London All my routines are quite prosaic before the actual process of writing, but I am always sitting at my desk. Most of my thinking and writing takes place at my desk, which has a southeast-facing window overlooking St. Martin’s Road in Stockwell, London. My desk isn’t tidy, but certain objects are always within reach. I keep a card, which was sent to me around 1990 by the late poet, Richard Caddel, keeper of the Basil Bunting Archive in Durham. On the card is printed Bunting’s advice to student poets. There isn’t a day when I don’t look at the card and think about some aspect of it. It’s engrained in me now, and I can recite it without thinking. At my back is a wall of bookshelves. These are some of my favorite books. I remember travelling into NYC on the train and going to Scribner’s when it was on Fifth Avenue—it would have been around 1983—just to buy The Collected Poems of Frank O’Hara. It was like my Bible. I still have that edition. O’Hara sits next to me when I write, as does Plath and Bishop. They are my companionable ghosts. |

|

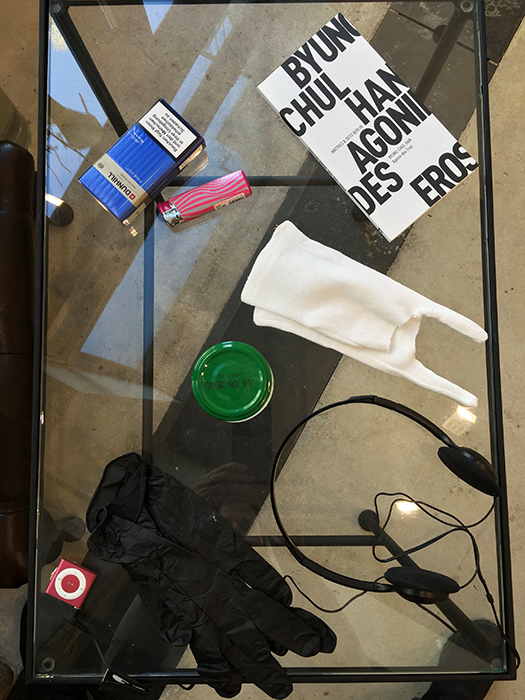

No. 14 Bjørn Hegardt Artist, curator, publisher, Berlin When starting a new creative process, my studio setting is important. The drawing depicts some of the stuff on my studio desk. Seemingly trivial items can play a crucial part: the right pen, brush, cup, glue stick, binder, tools, cables, adapters. I need those small things around me, in place, knowing the framework is there, to start working. |

Bjørn Hegardt, untitled, 2016, felt-tip pen on paper, 30 x 40 cm

|

|

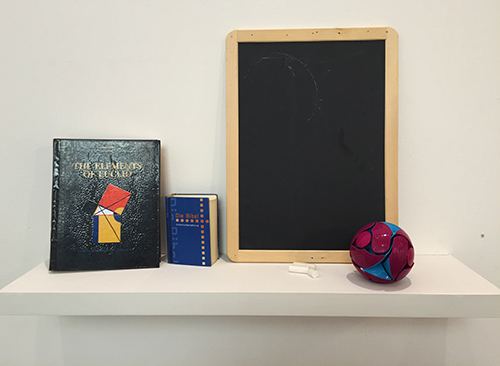

No. 15 Dr. Satyan Devadoss Mathematician, Claremont, CA Mathematics is viewed as a cerebral form of work, done with the mind and not with the body. There is a dualistic, gnostic notion of trying to separate thought from matter. I believe this way of thinking is not only wrong, but is an obstruction and stumbling block to pursuing mathematics. We must become engaged in mathematics with our whole bodies, for we are human, made of flesh and blood. My work requires a physical environment that promotes mental stimulation. A good board, excellent chalk, some books for inspiration, and some toys for design. All of these disparate physical objects play a large role in promoting mathematical output. |

|

No. 17 Amber Stucke Artist, Cincinnati, OH My daily routine are the words that I say to myself every morning: Thank You. I don’t draw every day, but when I do, I need to be able to access the state of mind of becoming to make my drawings. I do go for walks in the woods, read and cook quite a lot—but not every day. It is the words that I say that remind me, as a daily practice. |

|

No. 18 Thora Dolven Balke Artist, Berlin/Oslo When I’m moving my thoughts can wander and focus on nothing in particular. I like looking at surroundings passing by, through small lenses and low resolution that struggle to keep up with the shifting landscapes and light. How the camera fails to capture the depth of the visual experience and makes something new and other. |

|

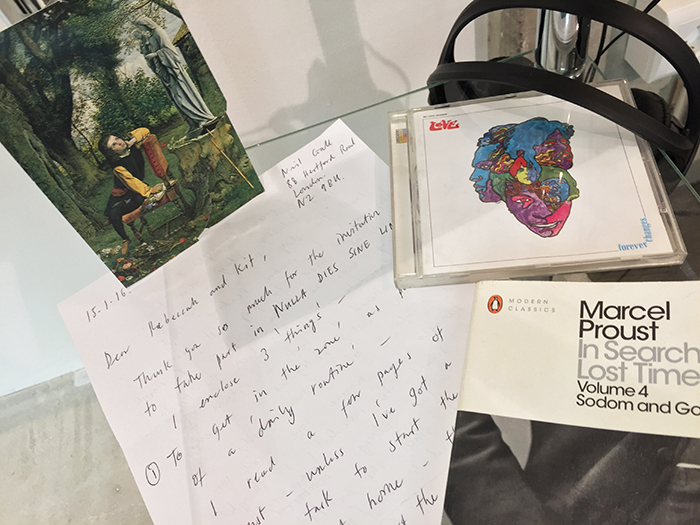

No.19 Neil Gall Artist, London Dear Rebeccah and Kit, 1) To get in the “zone” as part of a “daily routine”-- I read four pages of Proust—unless I’ve got a physical task to start the day. I work at home. The studio is at the bottom of the garden and it helps to separate things. 2) All artists seem to have postcards on their walls—like teenagers! Here is me: “Titian’s First Essay in Colour” by William Dyce. An otherworldly image. 3) Love “Forever Changes”—I don’t actually play this to start the day! However, I remember reading that Morrissey used to play it every morning when he woke up. I think this anecdote may have been the first time I heard of such a “ritual”—that was not religious. I even tried it for a while (same record) as a teenager. Maybe some kind of Satori would be revealed, I thought. Anyway I’ve always remembered the story and since the artist’s studio is part professional workshop/part teenager’s bedroom, I enclose a CD of said album. I seem to have lost my original LP. Choosing the ‘first’ record to play in the studio remains important to me—to set the mood—for ART! Best wishes, Neil Gall |

|

No.20

Massimo Morasso Poet, Genoa The artist, no matter of what sort or what his medium, must be moved by the nature of whatever art he practices. Among the artists, the poet, when he’s a poet, lives in a space between word and silence: the reciprocal implication of the “voice” and the “hush” create an internal balance in the case of writing (or aiming to write) poetry. I don’t regard myself as an exception to this grammar. On the contrary, I can see myself as a living example of it. Creative vitality normally comes to me via music, and this has to do with the poet’s task, as in my opinion “poet” means, at root, someone similar to a “carpenter of song” called to work mainly on rhythm, even more carefully, as it seems, than on images and concepts. To free my mind and concentrate myself, for a long time now I have become used to listen to a limited number of touching masterpieces of so-called “chamber music,” mostly string quartets, which I feel is its purest expression, and, among them, mostly the adagios. I don’t know why I prefer the adagios. I’ve never thought of such a motivation before. As a matter of fact, I can try to answer: they help my mind to get into a “quiet time” ruled by a silent, fertile dialogue between hearth and breath, and their (our) dynamics of expansion and contraction... So I owe a great debt to a few composers that accompanied me for years on my spiritual hunt. We know—it goes without saying—that the question “By what means or agency is poetry?” cannot be answered. |

But we know as well that poetry, when it is true poetry, involves the achievement of a particular “tone” and involves that achievement at an especially heightened tension. I am very far from thinking that the capacity of this “achievement” depends on the nature and the quality of several listenings, of course. I think it is only when I get empty and feel at ease listening to Corelli or Messiaen, for instance, it may happen that the “line of beauty” within me is moved, and that the material and immaterial elements of my mental reality mix together, preparing myself to host the “poetical word”—whatever it means. Usually, I work with words six days per week. And everyday my mood swings decide the pieces I’m going to choose. When I’ve made my choice, I often go on obsessively listening and re-listening to my “favorite” one, until I find the right (let’s say) “linguistic temperature” to begin to write. These six fragments are just a possible example of one of my regular weeks. And give a hint on how to conceive a short but not banal listening guide: Arcangelo Corelli: Concerto Grosso in Sol minore, Op. 6 No. 8 Anton Bruckner: Adagio aus dem Streichquintett F-Dur Anton Webern: Langsamer Satz Olivier Messiaen: Quatuor pour la fin du temps: 5 Louange à l'Eternité de Jésus Luigi Nono: Fragmente-Stille, an Diotima Arvo Pärt: Silentium |

|

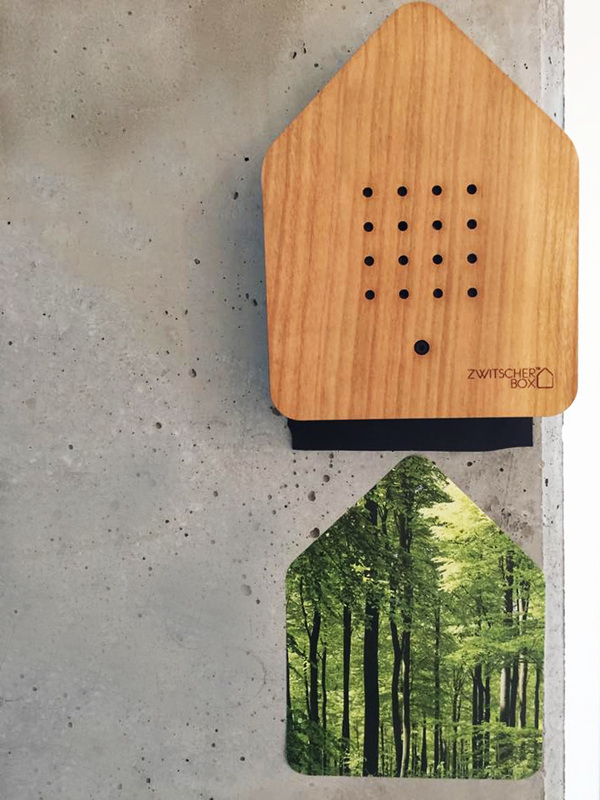

No. 21 Dr. Arndt Pechstein Neuroscientist, Berlin My anchor in creative work is nature. Its reflection of the present grounds me. Its aesthetics and brilliance of its forms and variety inspires me. Its unbiased existence puts me in a positive frame of mind. And it gives me a vision and a goal to preserve nature. The positive frame of mind is the motor for new ideas, for seemingly endless energy and for the drive to change things. By using different formats I attempt to surround myself daily with nature. In my office I look through a skylight above my desk at three treetops, which sway in the wind ten meters away. Various birds often use the branches as a place to rest. In spring and summer, I regularly work with the window open to be surrounded by the twittering of birds. I often even move my office outside. In the winter, I bring nature into the office and play the birdsong on digital media in the background. The view onto the treetops is there in the winter as well. Occasionally I simply leave the house and take a walk in the next park or forest. |

|

No. 22

Liliane Lijn Artist, London I do about 30 minutes of short form Tai Chi every morning when I wake up and a few yoga exercises. These keep me fit and possibly also grounded. Apart from that, I really don’t have time for inspirational rituals. I am desperate to find enough clear time to make work. Much of my work needs a lot of organization, research for materials and technological design, so when a gap opens in which I can draw or work by myself on an intensely creative side of the work, I jump into it without any need for preparatory ritual. There are two aspects to this situation. I believe that the main reason I don’t have time for preparatory rituals is that I am a woman artist, who has also had children. But perhaps, even women who don’t have children feel this urgency, this compulsion to create/work whenever they can. Seize the minute, not the day, since the day inevitably fills up with so many other obligations. I have observed with envy the lives of famous men so totally dedicated to their ‘art,’ who always seem to have some dedicated soul ready to look after their every daily need. Even when a woman is free to work at her ease, there is still the practical side of making things. Communication and all sorts of administrative jobs need to be off-loaded or taken care of before one can find the space and time to focus entirely on one’s art. For these reasons, I don’t need any rituals. The images I photographed were of torn and pulled together polythene coverings used to protect plants in a pineapple plantation above the lake of Tiberias in Israel. The resemblance to a draped female figure was startling. A figure that might perhaps have walked that very hillside thousands of years ago. A bride. The polythene also appeared as veils, curtains filtering light, partially obscuring the view. These sudden encounters with fertile material, whatever they may be, are the stuff of inspira-tion, the food for continuing my work. |

Installation view of Draped in Veils, Tiberius, Israel 2014,

digital scans, 42 x 29,7 cm and a double page from The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony by Roberto Calasso. Marked and annotated by the artist, digital scan, 29.7 x 42 cm. |

|

No. 25 Phil Minton Jazz/free improvisation vocalist, London Preparing my voice and brain for performance. A ritual, and a necessity. I do this daily, but never in airports. |

|

No. 26

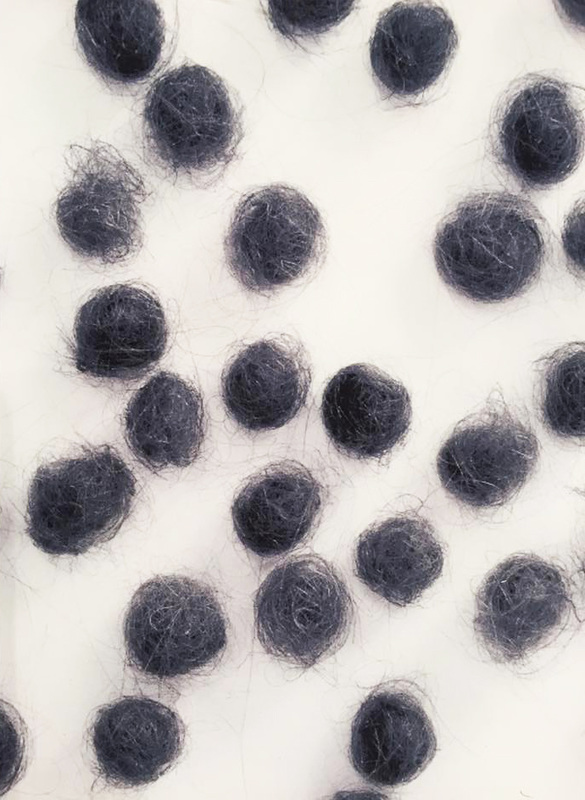

Béatrice Gysin Artist, Biel the daily rituals or: “what sets the mood” For years in the morning I’ve collected the hair in my comb and formed them into little balls. In approx. 2–3 weeks a hair ball is created. This ritual emerged years ago from the decision to prevent the clogging of the drain in the sink and especially to prevent the disgusting task of having to clear it when it becomes clogged. Over time, it has taken on a significance. With this simple gesture—the collection and forming of hair to a small balls—my day is begun. It tunes me in to continuity, time,patience, vigilance. An act that is absolutely worthless—something in the comb, tangled hair—in turn becomes something precious. The small ball fashioned slowly over an indefinite timespan has since tuned me in to the day, to acting and thinking. I’m learning that I must remain vigilant: changes require continuous attention. If I’m negligent, the old mess is quickly restored: the drain pipe clogs. So I have to keep up a day-to-day, repetitive action. I’m learning that the time flows. Or that I'm back in time to the next move. There are always more clumps. It’s dead material. It’s my hair. Transience in homeopathic doses so to speak. A single, small ball made of conglomerated lines. A Lines-Tangle. A swirl around a center. (A satellite?) A spatial drawing, one that depicts a completed period. A second ritual: I arrive in the studio: pull up, lights on, find traces on the drawing board of the previous day. The waste of sharpening, the tools, the paper. Maybe a drawing that has already begun. The examining glance. Continue drawing. Be vigilant. In the middle of the morning a coffee break. When I get stuck: sometimes it helps to take a look into the plant pots in front of the studio. What is growing in there? Today the hellebore are looking up at me. And snowdrops. (These power stations that grow high and undaunted through the snow). That they don’t freeze? A little rooting around in the earth. Something. Spending time with the plants. Sometimes it helps to see what I’ve drawn earlier, a couple of months, a year ago, a few years ago. How is the path? In which direction does it go? Consider. Sometimes it helps to see what others do. Spend time with books (often with the same ones). Or wander around in museums through the halls, looking for associations, searching for surprises. “Where is there some-thing for me?” It’s often the details that stop me. Perplexing, quirky, strange, unexpected. Or it pulls me to that group of paintings that I’ve already seen x-times, to have looked at that spot, that gesture, at that view, at that brushstroke. Appearances that I always look for and that fortify me. (For example Les Primitifs Francais in the Louvre.) Drawing exhibitions are for me energy-filling stations: it doesn’t matter how old the drawing traces are that I follow with my eyes. I can immediately enter their period. The power of creating a line appears to be as strong as ever. It reveals the pace in which it was put down. The manifestation of the lines allows me to vibrate or tremble, along with them, accordingly... In this way, gifted with energy of the drawings of others, I can return and immerse myself in my own. Sometimes it helps the getting stuck to sort things as a useful kind of ersatz activity: the pens in the box. The blue to blue. The green to green. Wash off the table and dispose of the sharpening waste. Stacking the drawings stored in boxes chronologically. Reorganisation on the outside leads to reorganization inside, creates free room for thought. What is the role of daily routine? The term “routine” is not the case for my working method. I understand “routine” as unquestionable ability, as technical proficiency. I’m starting my drawings, however, mostly without knowing where the lines will take me on their journey, to what extent surfaces will spread. Despite the decision at the beginning to take a certain direction, despite an intention, it is always accompanied by non-knowing, doubt, critical observation—the track and curiosity about how things will develop. While I’m writing these thoughts here, I wonder: maybe it's not important to draw “daily”? Maybe, it’s sufficient to remain vigilant. Ready. Wait until something is pressing forward. Until thinking becomes action. There is this inner film that never stops. Maybe, sometimes, it’s sufficient “to think drawing.” Important for me are the relationships, the moments of harmony. Sometimes I encounter them suddenly in a melody, in a sound, in a sentence. In book form, or as a literary voice. Sometimes it’s a place, or the photography of a place, that lets me breathe. Places of great expanse where nothing happens. Preferably snowy. If it’s snowing, I work with ease. Actually, I wait the whole year for the snow. Maybe my rituals to set the mood, to focus on work, ersatz activities are in anticipation of the chaotic, swirling snow, of the white, that transforms the world outside my studio window into a white, unmarked sheet of paper? A transformation that inspires me. |

|

No. 27

Mark Pascale Artist, curator, Chicago Napping or Cooking I don’t have a conscious method for being creative, or for cap-turing the creative moment. I have long believed that the creative process is organic and relational. One activity feeds into another. Sometimes, I have creative momentum in the moments just before sleeping—particularly when grabbing an impromptu nap. This is an infrequent activity. Early in my career, as I was establishing personal studio methods, I was also teaching myself to cook. Most of my cook-ing was based on memories of food I enjoyed growing up—Italian-American dishes for the most part. I enjoyed watching my grandmother in the kitchen. My graduate advisor was a serious gourmet—someone who could talk for two hours about flavored vinegars. I paid attention to his broad view in the kitchen. Creativity is largely intuitive, and cooking is creative, so I allowed myself to imagine the process of cooking as analogous to making art. Both require discrete operations and layering, and both are very hands-on. The tactile is important to me, as an element and as motivation. Since transitioning to work as a curator, cooking has become an even more important activity for me. The process of cooking keeps me connected to what I knew and felt when making art objects, and also satisfies right-brain exercise. It’s not verbally articulated, just as making art was never a verbal activity for me. People always ask me: what is my favorite thing—favorite artist, work of art, museum, gallery, whatever. I have very catholic taste, and this kind of question is embarrassing to me. It’s much easier to offer something that brings me great pleasure to make and consume, such as this winter soup that has become a staple in my cold weather repertoire. As always, the recipe is provi-sional, and subject to what is on hand, and how I finish it, but the elements listed here provide a good start. Hint, it’s even better using broccoli instead of cauliflower, and also not pureeing the entire pot of soup—leaving some solids. |

|

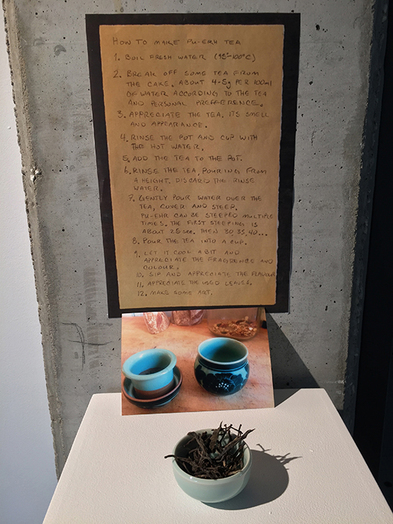

No. 28 Owen Schuh Artists, San Francisco Before I begin my work I like to have a cup of tea. I prepare the tea using a simple ceremony. This helps me calm the mind and bring awareness to the senses. This is very important, since my work deals so directly with mind and form. Tea itself is an important material in my work. I use it to stain much of my paper, which gives it a nice golden depth. My favorite type of tea is pu-ehr. (I prefer the raw, sheng-style pu-erhs.) They are often compressed into discs or bricks and are one of the few teas that improve with age. Pictured in the photo are my favorite brewing vessels. My wife and I bought them while traveling in Korea a few years ago. |

|

No. 29 Thomas Stammer Production designer, Berlin EXCAVATION—or on the ashes of thoughts grow the visions. For me it is what I do every day and what frees my mind again and again for new ideas: tear apart and throw away—make space for the new. EXCAVATION is one of my favorite words and a text on which I have been working for over 20 years. |

|

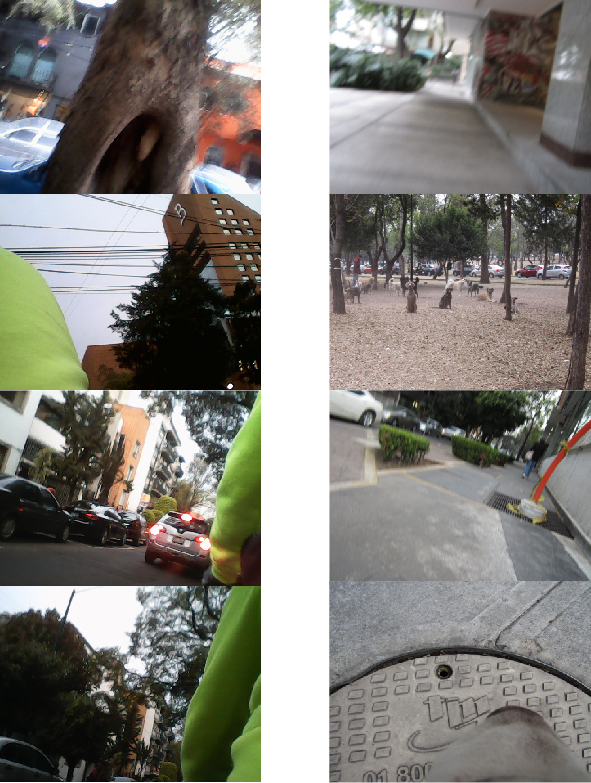

No. 31

Lorenzo Rocha Architect, Mexico City Routine In order to work, I need peace of mind. There are two specific moments in my daily routine that give me peace and contribute to clearing my mind before I start to work. The first one is taking my five-year-old daughter to her school. We take my bicycle. We have done that every weekday for the last two years. She sings or talks to me sometimes, but mainly she sits in her chair. The school is about one and a half kilometers away from our home. We always take the same route. The second moment is when I take my dog for a walk. He is ten years old and we have done that since he was a puppy. We have lived together in four different places, but we always go for a walk together. We have lived in the present apartment for the last two years. It is very close to a big park, so we either go there or just around the block if I don’t have much time. In fact, that’s exactly what we did today. For this exercise, I have asked my daughter to document our journey to school. She has a small wrist camera. After that, I attached a camera to my dog’s head and programmed it to shoot a photograph every thirty seconds during our morning walk to the park. I like these two parts of my daily routine, because they are repetitive, but at the same time they are different each day. It is like Heraclitus’s aphorism: “One cannot step into the same stream twice.” The same thing happens when I visit a building. I have often had the experience of being moved by a building on my first visit,disappointed with it on the second encounter and overjoyed by it on my third.' |

|

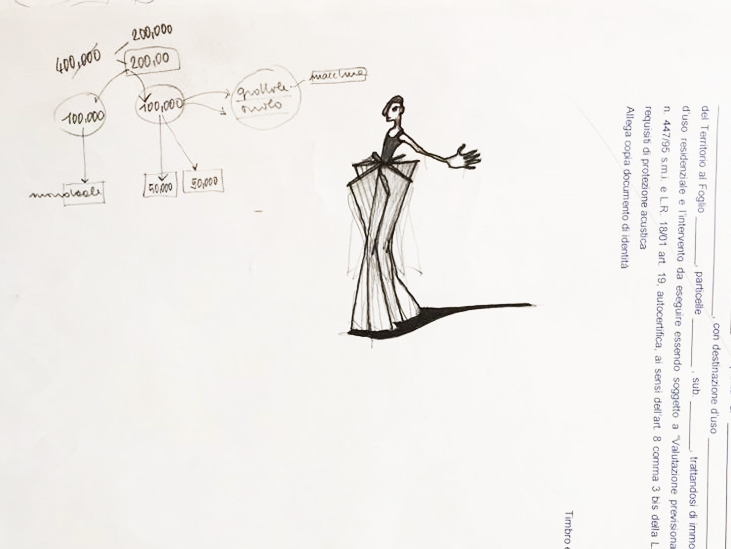

No. 32

Fabio Sonnino Set and costume designer, Rome WHAT STATE OF MIND To come up with my perfect state of mind, I must feel concentrated, but free to think about everything. HOW ACCESS I access it drawing sketches on recycled sheets of paper, on the white side, or on sheets of newspaper where I rediscovered classic images represented in popular language. WHAT ROLE Daily routine helps me to improve my spirit and the maximum speed of ideas. |

|

No. 33 Carrie Beehan Songwriter, performance artist, New York Inspiration comes from the fleeting sentence snippet in subway/store/street while passing, the tattooed statement on the woman's back, the tears and wailing of the broken-hearted stranger on the subway bench, the invitation to sealed rooms and private groups ranging from dens of inequity to offices in the Empire State Building. Every NYC ambulance siren a damaged or saved person, every fire engine and police siren the possibility of more anguish and shock or rescue and relief, every hustle a charged and concentrated need for an end destination, ruled by money, time, history, culture, status, profession, celebrity obsession, humor, pace, space, synchronicity, your personal trajectory and reruns of Saturday Night Live gems. |

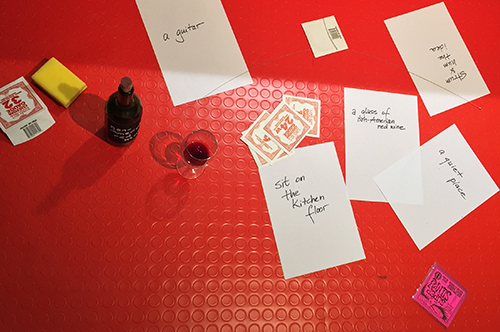

Details from Carrie Beehan's installation–an improvised kitchen

flooring and the paraphernalia of a songwriter. |

|

No. 34

Nanne Meyer Artist, Berlin Thoughts, ideas, inspiration, drawings do not come from naught. They are prepared. I level paths for them through concentration, so that something can appear that is not thought out. Often it is residue from my own working process, also remains, beginnings, words, scraps and edges, frivolous things that escape the wastebasket, as well as photos, maps, postcards, different kinds of paper and such, so many little bits from the periphery that catch my attention, that I pick up and collect. Ordered and spread out in piles and boxes on the table, they form the humus for associations in thought. Thinking is not made of words. It’s also whispering, seeing, rustling, feeling, moving and so on, deals with paper and tools, with pictures of all kinds, is vivid and tactile. A corner of my mind is brought to light on the table: place of possibility, waiting room, space of action, open for the unexpected and the connection of disparate things. In-between the lines push their way through. A drawing emerges. |

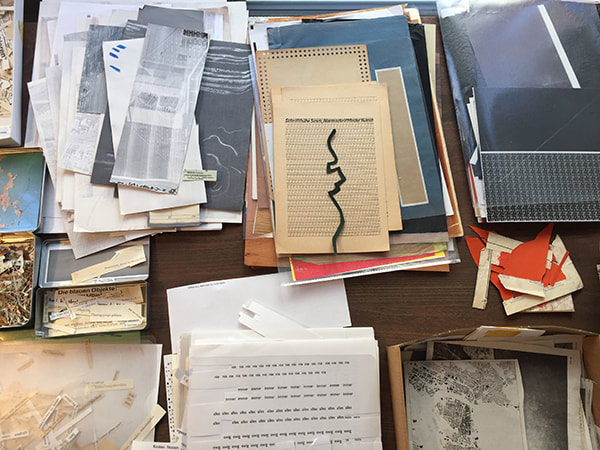

Detail from the installation by Nanne Meyer, which comprises

a table covered in boxes filled with various snippets. |

|

No. 35 Linda Karshan Artist, London/New York The counts, and their rhythms, are internal to me since 1994. They are that ‚moving figure assigned to me.’ They CONDUCT my movements and thoughts throughout the working day...and beyond. |

Linda Karshan– Choreographc Aspect (short), 2015

Study of Linda Karshan's feet, capturing the choreographic aspect of her practice for the documentary Linda Karshan – Choreographing the Page. Director Ishmael Annobil placed a handycam under Linda's worktable to capture her movements and their sounds. |

|

No. 36 Alexander Ross Artist, New York State Habits for Feeding Creativity • Give yourself time for wandering curiosity and playing with no goals in mind. • Make an effort to care about the small or unusual details wherever you may be. • Read all kinds of poetry, recent and past. • Make mental models of procedures. • Constantly look at new art and listen to new music. • A good formula for energy management; nap + espresso = productivity. • Always follow up on suggestions people give you for books, music, art, and film. • Occasionally reconsider cultural things you think you hate; taste changes. |

Alexander Ross, Oil on Imploding Maize, 2015,

digital image, 7 x 7.5 inches @180ppi |

|

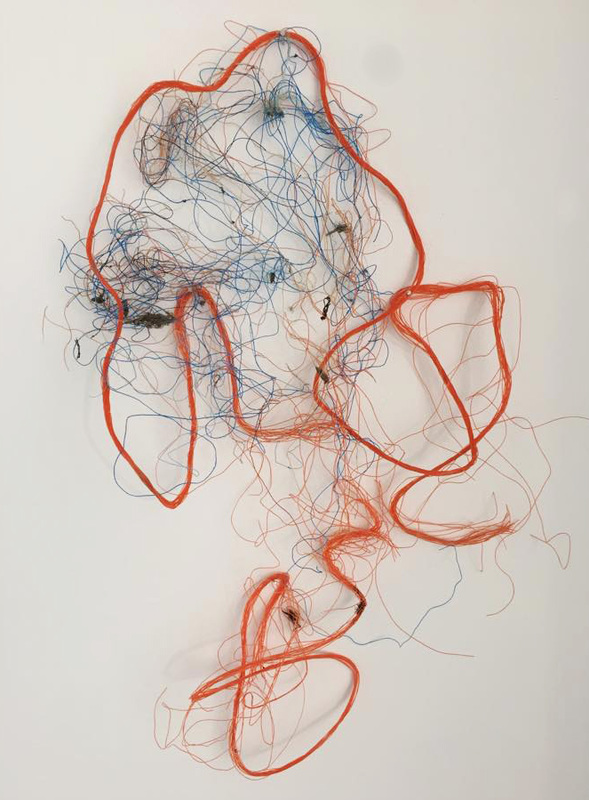

No. 37 Joseph Kosuth Artist, New York and London He lived at a little distance from his body, regarding his own acts with doubtful side-glances. He had an odd autobiographical habit which led him to compose in his mind from time to time a short sentence about himself containing a subject in the third person and a verb in the past tense. James Joyce

|

|

No. 38 Dr Paul Wrede Microbiologist, Berlin Caught in the net—freed by colors—there will certainly be scars Naturally, whenever I look at the orange-blue fragments of nets from the dyke on Pellworm Island, the lovely colored shape reminds me again to stay vigilant in my involvement with ocean preservation. Much that is beautiful and appealing is often a part of something dangerous. Good, I’m delighted by the harmonious colors, which lend me the energy to continually be able to battle what is dangerous and harmful. |